Humans regularly try to reason about what others want and what they might do next. Whether it’s merging into traffic, negotiating a salary, or coordinating in a team sport, success often hinges on understanding others’ intentions—and just as importantly, how they understand you.

When these mental models break down, the results can be inefficient—or even dangerous.

Think about two drivers approaching a merge:

- If both believe the other will yield, they might accelerate into a collision.

- If both believe the other will go, they might come to a stop, blocking traffic

These situations stem from mismatched beliefs about each other’s goals.

In our recent paper, “What Do Agents Think Others Would Do? Level-2 Inverse Games for Inferring Agents’ Estimates of Others’ Objectives”, we study how to formally model and infer agents’ beliefs about one another—not just what their goals are, but what they think others’ goals are. This richer modeling of belief can help explain (and prevent) inefficient, unsafe, or unexpected outcomes.

From Strategic Games to Third-Party Inference

We use dynamic games to model multi-agent interaction, where agents choose actions strategically given their objectives and expectations of others.

Our work focuses on a third-party observer—someone outside the game—trying to figure out what each agent is aiming for by watching how they behave. This observer doesn’t directly know the agents’ goals, so they must infer them from actions.

Here’s the key distinction:

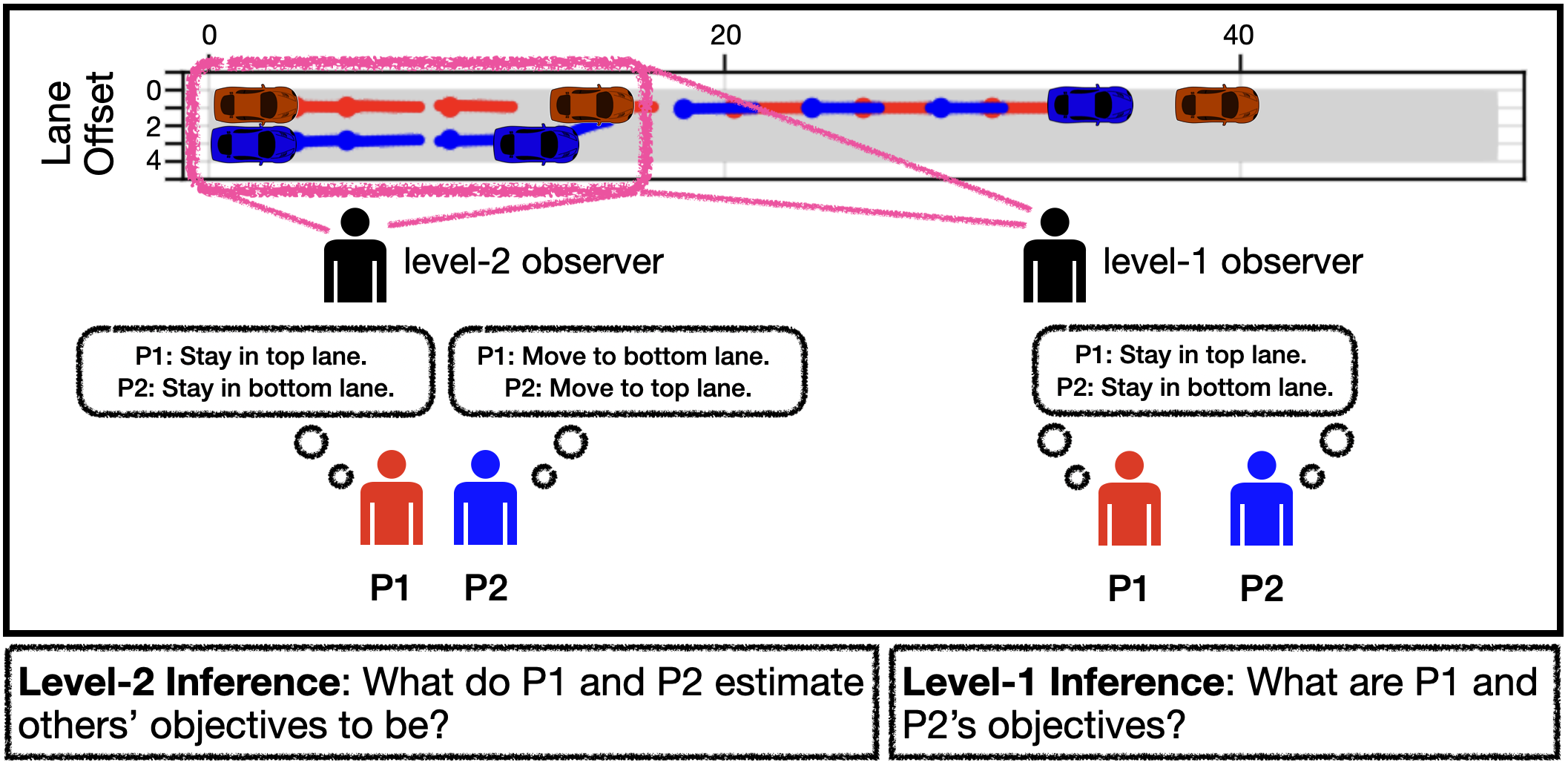

- Level-1 inference (what most inverse game methods do): The observer assumes that each agent knows the other’s objective (which is not known to the third-party observer). They simply infer those objectives from behavior.

- Level-2 inference (our approach): The observer also considers that agents may hold incorrect beliefs about each other’s objectives—and tries to recover both the true objectives and each agent’s belief about the other.

In our paper’s front figure (above), you can see how this plays out. On the right, a level-1 observer assumes the two drivers (P1 and P2) agree on each other’s intentions. On the left, a level-2 observer recognizes that each driver might be reasoning from a different (and wrong) mental model of the other—explaining why their interaction stalls.

Our Formulation

We define a Level-2 inverse game as follows:

Given observed interactions between agents, the third-party observer aims to infer:

- Each agent’s true objective.

- Each agent’s estimates of the others’ objectives.

This turns the problem into one of nested reasoning, where we model what each agent thinks the other is trying to achieve, and the game they believe they are playing with each other agent.

How We Solve It

This is a challenging estimation problem — non-convex even for simple linear-quadratic (LQ) games (which have analytical solutions). We tackle it by embedding a differentiable equilibrium solver (specifically, a Mixed Complementarity Problem solver like PATH) inside a gradient-based learning loop. This lets us simulate the agents’ decision-making process all the way through their beliefs, then adjust those beliefs and objectives until the simulated behavior matches what we observe.

What We Found

We evaluated our method on synthetic LQ games and a realistic lane-changing driving scenario. The results show:

- Level-2 inference is a more expressive framework and can capture outcomes based on mismatched gameplay that level-1 inference can not.

- When agents misunderstand each other, level-2 inference recovers those mismatches, giving the observer a more accurate and nuanced view of what’s happening.

- Level-1 inference can miss these belief mismatches, often misattributing hesitation or inefficiency to the wrong objective.

- Our method provides a plausible, structured explanation for deadlocks, over-cautious behavior, and unsafe maneuvers.

Why This Matters

As autonomous systems increasingly interact—with each other and with humans—it’s not enough to model just what agents want. We also need to model what they think others want.

By giving a third-party observer the tools to recover both goals and mutual beliefs, we open the door to systems that can detect and respond to misunderstandings before they cause inefficiency or harm. Whether in self-driving cars, multi-robot teams, or human-AI collaboration, belief-aware inference has the potential to make coordination safer, smoother, and smarter.

Read the paper here: arxiv.org/abs/2508.03824